Contents

The psychological school of behaviorism, particularly B.F. Skinner’s theory of operant conditioning, provides a powerful framework for explaining and modifying behavior, proving that consequences are the architects of our habits.

A New Approach to Psychology

In the early 20th century, the field of psychology was deeply invested in introspection, which was essentially a form of mental spelunking without a flashlight. A new school of thought called Behaviorism then emerged from the fog, suggesting that psychology should stop staring at its own navel and start using a stopwatch. Its central premise was shockingly straightforward: to be a science, psychology must focus on observable behavior, treating the unobservable mind like a beautifully wrapped but permanently locked box. This was a major change, akin to astronomers deciding to study only the light from stars and not the stars themselves.

Two names stand out in this new kingdom: John B. Watson, who christened the movement with its blunt name, and B. F. Skinner, its most methodical and patient high priest. They believed that all behaviors are acquired through conditioning, a slow dance of learning that occurs through interaction with the environment’s unblinking feedback. This theory proves that our actions are shaped by external factors, making us less like captains of our own ships and more like kites caught in a predictable wind. We learn to act in certain ways, sculpted by the world’s rewards and rebukes.

From early lab studies with strangely motivated animals to its modern-day application in our world, the principles of behaviorism, particularly operant conditioning, provide a powerful and structured tool to explain, predict, and modify behavior, acting as a kind of user manual for the creatures we are. I myself will explain this in the following sections, revealing the invisible strings that make us move.

The Foundations: Classical Conditioning and the Law of Effect

John B. Watson’s early work focused on what he called respondent behavior, which are the body’s automatic reflexes that operate without ever consulting the brain’s fussy management team. This form of associative learning is known as classical conditioning, a process that can teach your stomach to rumble at the mere jingle of a food delivery app. For example, a doctor taps your knee with a small hammer and your leg kicks automatically, a simple puppet show starring your own nervous system.

This extends far beyond physical jerks. A person who has a bad experience with a dog during their boyhood might feel a surge of fear whenever they see any dog in the future, effectively turning every happy, tail-wagging Golden Retriever into a four-legged ghost. The association is made involuntarily, a memory etched not in the mind but in the gut.

Before Skinner built his empire, Edward Thorndike established the background for operant conditioning with his “Law of Effect,” a concept so simple it feels like it was discovered rather than invented. He proposed that any behavior followed by favorable consequences becomes more likely to occur again, while behavior followed by unfavorable consequences tends to fade away like a forgotten pop song. This simple idea, that success breeds repetition, was the humble seed from which Skinner’s entire forest would grow.

B.F. Skinner and the Dominance of Operant Conditioning

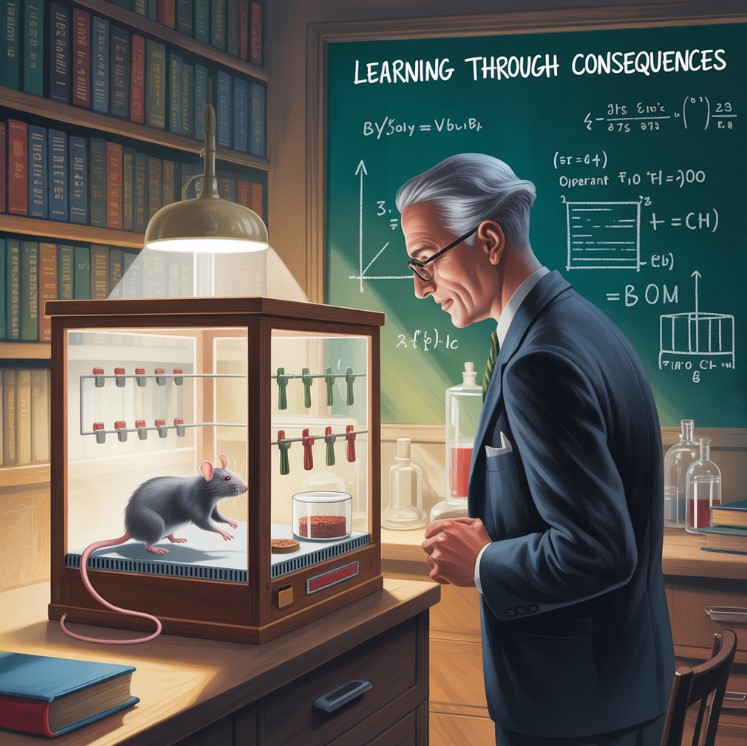

B.F. Skinner, a leading psychologist with the patience of a glacier, did not just agree with Thorndike; he expanded that idea into a comprehensive theory he called Operant Conditioning. Operant conditioning, also known as instrumental conditioning, is a method of learning that relies on the hard math of rewards and punishments for behavior. It relies on the premise that an association is made between a voluntary action and the universe’s reply to that action.

To study this, Skinner invented an operant conditioning chamber, a beige, minimalist studio apartment for rodents or birds. The box, often called a “Skinner Box,” typically contained a rat or a pigeon, where the animal could operate a device like a lever to receive a reward or avoid a mild electric shock, making it a tiny casino of consequences. A recorder outside the chamber recorded the animal’s responses automatically, its scratching pen charting the subject’s ambition and despair. The slope of the line on the recorder would indicate the rate of response, turning learning into a line on a graph that climbed toward enlightenment, one pellet at a time.

The Core Principles: Reinforcement and Punishment

The entire engine of operant conditioning runs on two fuels: reinforcement, which tells a behavior “do that again,” and punishment, which screams “never do that again.”

Reinforcement (Strengthening a Behavior)

Reinforcement is any event that strengthens the behavior it follows, making it the hero of the operant conditioning story.

- Positive Reinforcement: This involves the addition of something desirable, like getting a paycheck for your work or your cat deciding to grace you with its presence.

- A parent giving praise for a child who helps clean their room is using positive reinforcement, a verbal cookie for good conduct.

- An employee receives a bonus for high performance, a clear signal from the corporate gods that they are pleased.

- Everybody likes receiving a favorable treat, a universal truth that applies equally to puppies and chief executive officers.

- Negative Reinforcement: This involves the removal of an unpleasant stimulus, which is not punishment but rather a sweet, sweet relief.

- A student finishing their homework to stop the nagging from a teacher is reinforced by the sudden, beautiful silence.

- The loud noise in a car stops once you buckle your seatbelt, training you to buckle up through the power of annoyance removal.

Punishment (Weakening a Behavior)

Punishment is any consequence that weakens the behavior it follows, serving as the story’s stern and often misunderstood villain.

- Positive Punishment: This involves the addition of an unfavorable outcome, like a spanking or the sinking feeling you get after saying the wrong thing at a party.

- An angry parent scolds a child’s misbehavior, adding a verbal sting to the situation.

- A rat presses a lever and receives a hot shock, a surprisingly effective lesson in cause and effect.

- Negative Punishment: This involves the removal of a desirable stimulus, essentially putting your privileges in a time-out.

- A child who acts out may lose their phone privileges, a punishment that feels like being exiled to the 1990s.

- Others might be punished by having their car keys taken away, turning them back into a pedestrian against their will.

The Importance of Timing: Schedules of Reinforcement

Skinner realized that the timing of a reward has a direct impact on behavior, proving that when you get paid is just as important as what you get paid.

A Continuous Schedule reinforces a behavior every single time it occurs, which leads to fast learning but also gives up the moment the rewards stop. A Partial Schedule, however, reinforces a response only part of the time, which results in slower learning but creates a behavior that is stubbornly resistant to quitting, much like a hopeless romantic.

There are four main kinds of these powerful partial schedules:

- Fixed-Ratio (FR) Schedule: Reinforcement is delivered after a specific number of responses, making work feel like filling up a progress bar to get a prize. (e.g., A worker gets paid for every five boxes they pack, turning labor into a simple, countable task).

- Variable-Ratio (VR) Schedule: Reinforcement is delivered after an unpredictable number of responses, a design that has single-handedly funded the entire city of Las Vegas. (This creates high, steady rates of responding, because the next pull of the lever could be the jackpot).

- Fixed-Interval (FI) Schedule: Reinforcement is delivered for the first response after a specific amount of time has passed, which is why productivity mysteriously skyrockets right before a deadline. (e.g., A weekly paycheck, which does little to motivate you on a Tuesday morning).

- Variable-Interval (VI) Schedule: Reinforcement is delivered for the first response after an unpredictable interval of time, like a pop quiz that forces you to study all the time, just in case. (e.g., A manager who occasionally drops by and offers praise, turning the workplace into a theater of perpetual competence).

Real-World Application: Behavior Modification in Everyday Life

The principles of behaviorism are not confined to a lab; they are the invisible architects of our daily routines.

In education and with family, teachers use these ideas to conduct the chaotic symphony of a classroom. They can reward a quiet student with praise, shaping an entire room of children with a currency of smiles and stickers. The process of shaping helps teach complex skills, because you don’t learn to clean your room all at once, you learn by first being praised for not leaving a wet towel on the floor.

In clinical and therapeutic settings, these techniques are used to help people change undesirable behaviors, acting as a kind of reverse-engineering for bad habits. A therapist might work with someone to overcome a phobia by slowly exposing them to the feared thing, proving that a spider is just a spider and not a tiny monster sent from another dimension to critique your dusting.

Anybody who has tried to train a dog to sit has used operant principles, turning a handful of treats into a PhD in canine obedience. At work, the entire system of salaries and bonuses is based on behaviorist principles, designed to make you a more efficient cog in the great machine. Nobody works for nothing, a fact that is both profoundly simple and deeply complicated.

The End of a Response: Extinction and Other Concepts

What happens when a reinforcer for a behavior is completely removed? The behavior will undergo extinction, slowly fading away like a photograph left in the sun. However, after a rest period, the behavior might suddenly reappear in a phenomenon known as spontaneous recovery, popping up again like a ghost to see if anyone is listening.

It is important to remember the difference: Classical conditioning involves automatic behaviors tied to a preceding stimulus, while operant conditioning involves voluntary actions guided by a subsequent consequence. One is a reflex, the other is a strategy.

Conclusion: A Recap of Behaviorism’s Enduring Legacy

The behaviorist movement, from its brash beginnings to its dominance under Skinner, fundamentally changed the course of psychology by insisting that it look, not think. Its principles provide a clear, observable framework for understanding how we learn, a blueprint showing that consequences are the chisel that sculpts the marble of our being.

The major criticism of behaviorism is its neglect of internal cognitive factors, treating the mind as a “black box” that is ultimately none of its business. It treats thoughts and feelings like mysterious vapors that are irrelevant to the observable mechanics of action.

Yet, even with this comment, nobody can deny its lasting influence, a testament to the power of a simple, and sometimes unsettling, idea. As we have seen, the principles of behaviorism are all around us, operating quietly in our homes and jobs. To recognize them is to better understand the forces that write the code for our daily lives. So, the next time you give your dog a treat for rolling over, you can tell yourself you are acting as a behaviorist, a scientist in a bathrobe, proving a theory with a biscuit.